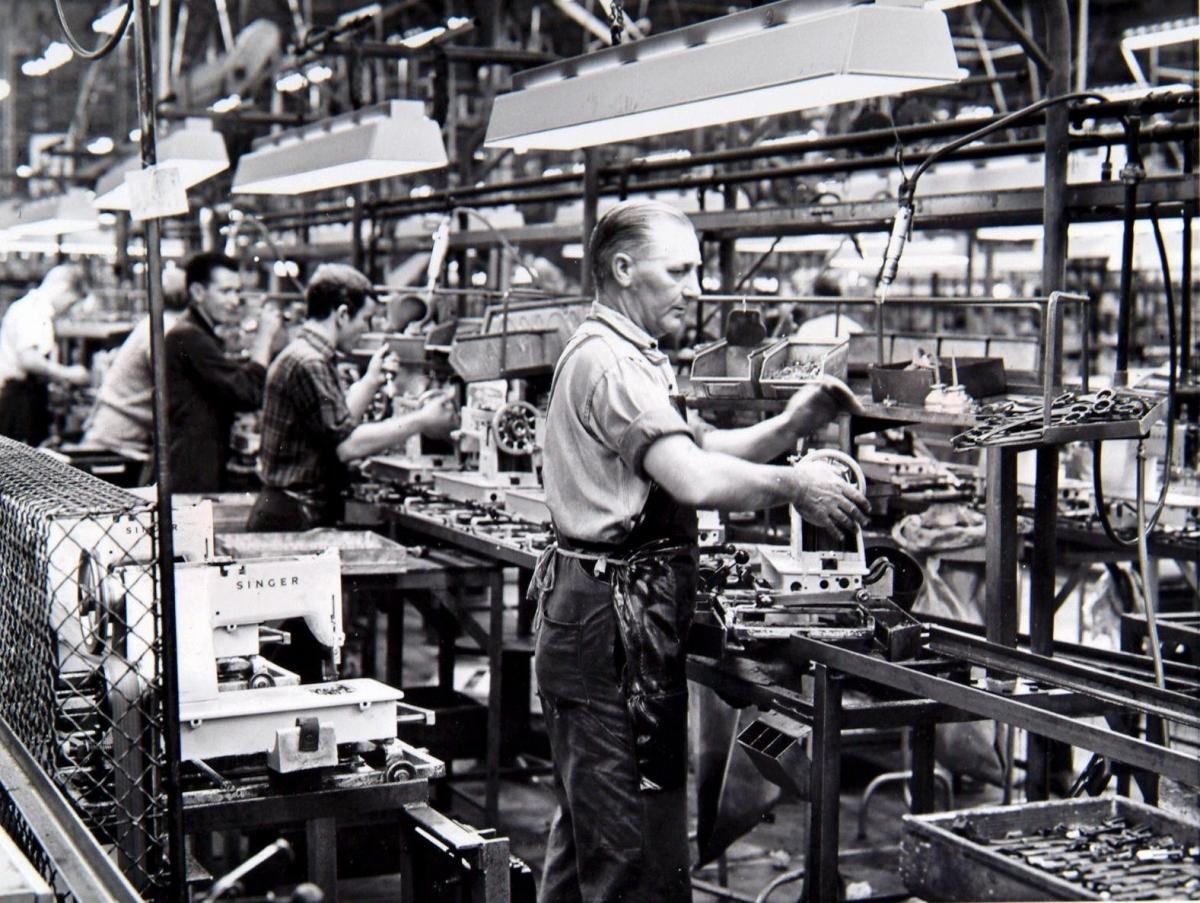

“END of the line” was the main front-page headline in the Glasgow Herald of October 13, 1979, when the closure of the huge Singer sewing-machine factory in Clydebank was announced, with the loss of 3,000 jobs.

Company executives put much of the blame on what it said was the workers’ low productivity. The market, they added, had declined because of changing fashions and cheap, ready-to-wear clothes, mainly from the Far East.

Bruce Millan, who had been Scottish Secretary of State under Labour until the previous May, accused Singer management of breaking a “solemn promise” over the factory’s long-term future, given to him when Labour were in power in 1978. He said they had promised to “maintain a substantial operation” in Clydebank, and he now called on the Thatcher government to intervene.

The STUC said the Singer plan, the beginning of a two-year, worldwide restructuring by the firm, could turn Clydebank into the Jarrow of the 1970s. STUC general secretary James Milne said the closure was a disaster, and said the trade union movement to fight to reverse the decision.

The factory had long been a key presence in Clydebank, having been built in 1882-1885. By 1885 it was the largest factory in the world. Its products were sent all over the world.

The famous Singer clock tower (main image) was a landmark, but it was demolished in 1963 to make way for new workshops.

In June 1978 Singer wanted to cut its Clydebank workforce from 4,800 to some 2,000 by 1982, because of the shrinking market and strong Japanese competition. It took powerful UK government pressure, including a personal exchange between Prime Minister Jim Callaghan and US president Jimmy Carter, to persuade them to think again.

* More tomorrow

Read more: Herald Diary

Why are you making commenting on The Herald only available to subscribers?

It should have been a safe space for informed debate, somewhere for readers to discuss issues around the biggest stories of the day, but all too often the below the line comments on most websites have become bogged down by off-topic discussions and abuse.

heraldscotland.com is tackling this problem by allowing only subscribers to comment.

We are doing this to improve the experience for our loyal readers and we believe it will reduce the ability of trolls and troublemakers, who occasionally find their way onto our site, to abuse our journalists and readers. We also hope it will help the comments section fulfil its promise as a part of Scotland's conversation with itself.

We are lucky at The Herald. We are read by an informed, educated readership who can add their knowledge and insights to our stories.

That is invaluable.

We are making the subscriber-only change to support our valued readers, who tell us they don't want the site cluttered up with irrelevant comments, untruths and abuse.

In the past, the journalist’s job was to collect and distribute information to the audience. Technology means that readers can shape a discussion. We look forward to hearing from you on heraldscotland.com

Comments & Moderation

Readers’ comments: You are personally liable for the content of any comments you upload to this website, so please act responsibly. We do not pre-moderate or monitor readers’ comments appearing on our websites, but we do post-moderate in response to complaints we receive or otherwise when a potential problem comes to our attention. You can make a complaint by using the ‘report this post’ link . We may then apply our discretion under the user terms to amend or delete comments.

Post moderation is undertaken full-time 9am-6pm on weekdays, and on a part-time basis outwith those hours.

Read the rules here